INTRODUCTION: QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

Show the students a globe or a global map and ask them if they can identify the equator.

Q: Where are the poles? Where does the equator lie relative to the poles?

A: The equator is the line or circumference on the globe half way between the poles.

Figure 5: Illustration of a globe and the position of the equator relative to the North Pole (US Government).

If possible, let the students use an online map tool to investigate geographic and satellite images of the equatorial region. The map tool may also be projected on a single computer. Here are some possible map services with satellite imagery:

https://maps.google.com https://www.arcgis.com/home/webmap/viewer.html?useExisting=1

Q: Can you name countries that touch the equator? Do you know any cities close to it?

A: e.g. Ecuador (Quito, Galapagos), Brazil, Gabon (Libreville), Congo, Uganda (Kampala), Kenya, Malaysia, Indonesia.

Q: What is the typical vegetation there?

A closer look at the satellite images helps to answer the question. A: Rainforest.

Q: What is the typical weather there (humid or dry, cold or warm)?

A: Humid and warm, with lots of rain.

Q: Can you think of a reason for why it is so warm there all year? Show them a model of the Sun-Earth-System (Figure 5).

A: The Sun is the main heating source. Near the equator, it is always almost directly above.

Q: The air is heated by the hot surface of the Earth. What happens with hot air? Imagine a hot air balloon.

A: Warm/hot air rises above cold air.

Q: How would you be able to recognize that air rises?

A: Wind

Figure 6: Illustration of the Earth by the Sun. Looking from the equator, the Sun is almost always directly above (Przemyslaw ‘Blueshade’ Idzkiewicz, ‘Earth-lighting-equinox EN’, solar light beams at different latitudes added by Markus Nielbock, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode).

ACTIVITY 1: FLYING FLAMES

WARNING! This activity is only suitable for students who are responsible enough to handle a flame. Be sure to provide a fireproof environment and to supervise the students during the experiment. Lighters or matches should be distributed only to small groups of students at a time. If in doubt, the experiment should be demonstrated by the teacher.

Smoke detectors may have to be disabled for this activity.

Use a fireproof surface. A china plate or a piece of tinfoil may be used to protect the surface of normal desks or tables.

In this activity, the students will experience how warm air rises above cool air. The hot air produced by a burning piece of very light paper produces its own uplift and rises up. This experiment should produce a qualitative result, that is, the exact uplift force is not so important.

Gather the following items, one set per group (or one for the teacher only, if carried out as a demonstration): - paper handkerchief, napkin or dual chamber tea bag - matches or lighter - plate or/and tinfoil - scissors

Figure 7: Illustration of the instructions (own work).

A video with instructions and explanations is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TKF3OKxwM8g

Distribute the students in groups of two (suggested).

- Prepare the wick:

a. Paper handkerchiefs and napkins consist of several layers. Take only one and cut off one quarter.

b. If a tea bag is used, cut off the top and empty the bag. Unfold it. - Form a tube (napkin, handkerchief, tea bag) of a few centimeters and put it on the plate, standing upright. It should stand stably. Avoid abrupt and fast movements to prevent the moving air from blowing the wick away.

- Light it.

Discuss with the students what happened. Let the students describe in detail what they saw. While the wick burns down, the paper lifts off at some point.

Q: What happened to the air around the burning paper?

A: It was heated.

Q: What happens with heated air?

A: It rises.

Q: Can you explain why in the end, the burning paper lifted off?

A: It was dragged along with the rising air.

ACTIVITY 2: UPDRAFT TOWER

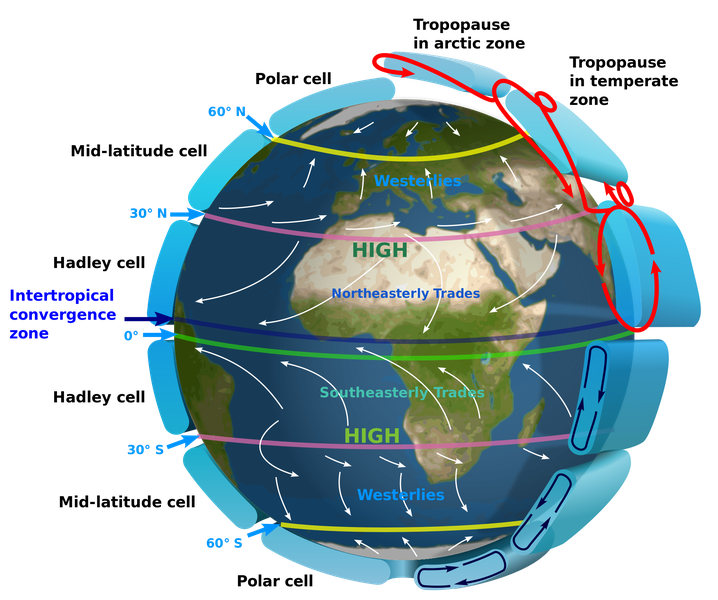

This activity demonstrates how heated air rises. As long as the heating source is present, a continuous updraft of the heated air is generated. The students will experience this phenomenon by building a model of an updraft tower. Subsequently, the concept of air circulation can be used to explain the process of terrestrial atmospheric circulation systems and the Intertropical Convergence Zone.

Tell the students that they will now build a model of such a tower. Tell them that it is a good way to demonstrate vertical wind on a small scale.

Gather the following items, one set per group: - scissors - flat nose pliers, if available - glue (for cardboard) - pencil or similar pointed object - aluminium wrap of a tea light - drawing pin

For either of the following alternatives:

Alternative 1 - cardboard tube (inner part of a kitchen roll) - black paint and brush or black coloured paper - one piece of cardboard (approx. 1 cm wide, 8 cm long)

Alternative 2 - construction template provided with this sheet - black cardboard (22 cm × 20 cm) - one piece of card board (approx. 1 cm wide, 12 cm long, see template)

Figure 8: Items needed for building an updraft tower model (Picture: M. Nielbock).

Construction Template (scaled down version, original version to be attached)

Building Instructions

Alternative 1:

The first version may be simpler to produce but may not be as effective, because the cardboard tube used in this example may a bit too narrow.

1. Paint the outside of the cardboard tube black or glue it with black paper.

Alternative 2:

The second version is especially designed to match the diameters of the tower and the fan.

1. Prepare the black cardboard according to the construction template provided.

2. Roll the cardboard perpendicularly to the hashed area.

3. Glue the tube at the hashed area.

4. Cut out the grey areas or cut them from bottom to top and fold them up to form flaps.

Figure 9: Set of items with the tower already built (Picture: M. Nielbock).

Common steps:

5. Now we produce the fan using the tea light wrap. This part is quite delicate and has to be done very carefully.

6. Cut 16 equal sections into the walls of the tea light wrap.

7. Flatten the sections outside to the bottom of the wrap.

8. Extend the cuts to the inner circle of the bottom of the wrap.

9. Press the pencil exactly at the centre of the fan to form a small dent. Be careful not to punch a hole.

10. Bend all 16 wings of the fan around an axis from the centre to the edge. Use the pliers if available.

11. Punch the drawing pin through the centre and from the back of the small piece of cardboard.

12. Glue the small piece of cardboard to the inside at the top of the tube. It should form an arc.

Figure 10: Set of items with the tower and the fan (Picture: M. Nielbock).

13. Put the fan on top of the drawing pin.

14. Balance the fan by bending the wings up and down.

Figure 11: The finished updraft tower model (Picture: M. Nielbock).

15. Illuminate the side of the tower with a strong lamp.

16. Watch the fan rotate.

Discuss the results with the students.

Q: Why does the fan rotate?

A: The air inside the tower is heated up and streams upward.

Q: How is the air heated? Remember that the lamp does not shine inside the tower.

A: The lamp heats the black tower, which in turn heats the air inside.

Q: What are the holes at the bottom for?

A: They permit the tower to be replenished with fresh air.

Q: If you compare this with the situation on Earth, what does the Sun do in the belt around the equator? What happens with the surface and the air above?

A: The Sun heats the ground which, in turn, heats the air. Just like the model of the updraft tower, the heated air rises and produces a continuous updraft of air.

Q: Can you imagine what happens with the air when it reaches high altitudes?

A: The air cools down and the moisture condenses to rain.

Q: Coming back to the updraft tower: it had flaps at the bottom to allow the air in the tower to be replenished. The same happens on Earth. What do we call horizontal air flows?

A: Wind.

ACTIVITY 3: WORKSHEET- THE WIND ENGINE OF THE EARTH

We have seen in the experiments that a heat source can heat up air and cause an upward flow. The same process happens on Earth.

Q: Look at Figure 5. Where on Earth does the Sun heat most efficiently?

A: Around the equator

Q: Heating the air directly is quite inefficient. When you think about the updraft tower experiment, the lamp did not heat the air. Describe the process by which solar energy eventually heats the air.

A: The irradiation from the Sun heats the ground, which in turn heats the air. This is more efficient next to the surface than at higher altitudes.

Q: Which part of the atmospheric layers is heated strongest?

A: The one next to the surface.

Indicate the correct attributions:

The air close to the surface of the Earth is warm/~~cold~~.

The air at high altitudes above the ground is ~~warm~~/cold.

Q: What happens with the air close to the surface? Consider the temperature differences between low and high altitudes.

A: It rises above cooler air.

Q: Warm air can store more water than cold air. What happens when air rises into the higher layers of the atmosphere? Think of boiling water at home when the hot air meets the cold air or cold surfaces.

A: The water vapour condenses, first to clouds and eventually to larger drops and rain.

Q: Can you explain why the equatorial regions of the Earth experience so much rain during the year?

A: Warm humid air is driven up to cooler atmospheric layers where the water condenses to rain. This is a process that works almost all year.

Q: This region around the equator is also called the Intertropical Convergence Zone, abbreviated as ITCZ. At some point, the air cannot rise any higher. It is diverted north and south. At these high altitudes, the air constantly cools down. What happens with cold air?

A: Cold air drops closer to the ground.

Q: We just mentioned that cold air can store less water than warm air. Can you explain why the desert areas north and south of the equator are so dry? What happens with the air when it drops back to the surface?

A: When the warm air rises up to cooler layers, it cannot store water as efficiently falls down as rain. The air is dried by this process. When this air drops, it is heated up and potentially can store more water. Without replenishment with humid air, the air becomes even drier.

Q: Back at the surface, the air streams towards the equatorial region, where they converge (ITCZ). These are winds we call ‘trade winds’. Can you imagine why they are called this?

A: Trade winds are a fairly constant phenomenon that helped cargo ships to sail long distances. Its direction is fairly stable as well, so ships do not get lost often.

Q: Try to predict what would happen with the winds and weather, in general, if the temperature continues to rise.

A: Temperature is the main engine of updraft. Higher temperatures also cause more water to be evaporated and enrich the air. As a result, one should expect more extreme phenomena related to the ITCZ.

Q: This is actually happening right now. It is called global warming. Explain what would happen if we do not stop this process.

A: This aspect of the climate change will lead to more severe weather, especially near the tropics.

We have constructed an entire circulation system that begins and ends at the equatorial region. This system is called the Hadley Cell. Can you draw a schematic with the most relevant elements and processes? Use the prepared sketch below as a starting point.